Forty years after Calvin’s death, the family members discover that they are trying to understand what happened. Posen, in turn, poaches Franny’s family history and uses it as the basis of his next novel, “Commonwealth,” much to the horror of the entire Cousins-Keating clan. The book loops around this event: All of the Cousins and Keatings remember Calvin’s death differently, depending on their proximity to it, and their memories define the shape of each person’s life.įranny goes on to become the live-in mistress of the much-older literary legend Leon Posen - a needy, misogynist drunk, Patchett’s amusing little jab at the mythic Great American (Male) Novelist. “Not that the days were always fun, most of them weren’t, but they did things, real things, and they never got caught.”Įventually, though, the children do get caught, but only when it’s too late and Calvin is dead. “It was like that every summer the six of them were together,” Patchett writes, capturing the essence of a lost childhood. They feed the pesky littlest brother Benadryl they steal their father’s gun they sneak out and swim unsupervised in lakes. no one can quite grasp where the innate truth of a story might lie. Patchett is interested in how the past fuses with the present. Unpretentious and ultimately heartbreaking, miniaturist but also sprawling, “Commonwealth” is a story about family stories: how they shift based on the person who tells them, and how they can slip from your grasp and become part of someone else’s narrative. Loosely inspired by Patchett’s own Los Angeles childhood - and the divorces and remarriages of her parents - “Commonwealth” is a beautiful puzzle box of a book, one that doesn’t clearly fit together until all of a sudden, midway through, it does. The party that starts as a kid’s celebration ends with an illicit kiss that will have repercussions still being felt 50 years later.

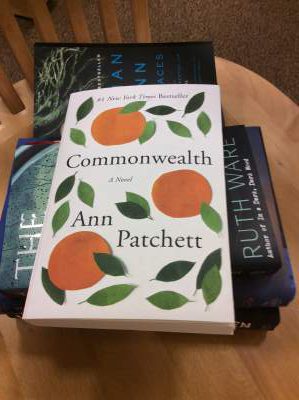

In Ann Patchett’s bravura rendering, the two are dangerously intoxicating, triggering a kind of giddy, selfish blindness. Sunshine and citrus: In literary California, these have long been potent symbols of the abundant promise of life in the west. Suddenly, the orange trees that grow around the neighborhood are being stripped for juice, drunk adults are dancing in the midday sun and even the Catholic priest is comparing the bounty to the miracle of fishes and loaves. “Commonwealth” begins with a kind of fever dream: A christening party in 1964 Los Angeles that takes a left turn when a giant bottle of gin is introduced.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)